How does Google's accessibility team work? A chat with the Director of the Global Accessibility Team

According to WHO, more than 1 billion people worldwide have some kind of disability. According to [WHO](), more than [1 billion people]() worldwide have some kind of disability, representing 15 per cent of the population; this number will rise as people age and live longer. In the Asia-Pacific region specifically, there are currently approximately 690 million persons with disabilities, far more than in any other region of the world.

As one of the world's leading technology companies, Google's products are used by millions of users, and its Android system is closely linked to the daily lives of countless people. Therefore, accessibility needs are always on Google's mind. What is Google doing in this area and how does it view and coordinate accessibility issues internally?

Recently, Eve Andersson, Senior Director of Google's Global Accessibility and Inclusion team, shared her work and insights at an online sharing event that Minority was invited to participate in.

Eve Andersson, Senior Director of Google's Global Accessibility and Inclusion TeamEve Andersson has been with Google since 2007 and has been involved in accessibility-related work for nine years, starting in 2013. Talking about her understanding of this work, Andersson says she has been repetitive strain injury (RSI, which refers to repetitive use, vibration, compression or prolonged fixed posture causing damage to the musculoskeletal system or nervous system), and for a few years had great difficulty typing, often using voice input to complete daily tasks.

Eve Andersson, Senior Director of Google's Global Accessibility and Inclusion TeamEve Andersson has been with Google since 2007 and has been involved in accessibility-related work for nine years, starting in 2013. Talking about her understanding of this work, Andersson says she has been repetitive strain injury (RSI, which refers to repetitive use, vibration, compression or prolonged fixed posture causing damage to the musculoskeletal system or nervous system), and for a few years had great difficulty typing, often using voice input to complete daily tasks.

As such, she clearly understands that accessibility is a broad field, not just for people with permanent disabilities, but also for groups with temporary mobility impairments due to injuries, illnesses and situations. The same tools have individualized purposes and uses in different hands, and products built for accessibility may be useful to all.

Anderson currently leads the Central Accessibility Team. This team includes software engineers, product and project managers, UX (user experience) designers, researchers, testers, and other diverse roles, and is responsible for gauging the accessibility of Google products and coordinating training, testing, and consulting on accessibility topics so that product teams can incorporate accessibility principles in the design and release of their products. ](https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/ui/accessibility/) in the Android developer documentation is authored by her team.

Google Accessibility Center team incorporates process and cultural accessibility thinking

Google Accessibility Center team incorporates process and cultural accessibility thinking

In her sharing, Anderson highlighted Google's mindset of integrating accessibility into its workflow. She quoted Google CEO Sundar Pichai as saying, "Google doesn't consider any problem solved as long as someone is still suffering from it."

As an example, Anderson said that every new engineer who joins the Google Engineering Center needs to participate in "hands-on" accessibility workshops to learn about mobile and web accessibility, and that Google also hosts regular events to enable employees to acquire more accessible development skills. In the company's in-house UX Accessibility Academy, developers and accessibility researchers have the opportunity to get together, work on discussions, and put ideas into practice.

Anderson also described how Google itself is practicing accessibility principles in its workplace culture. The company has started an internal Office Accessibility Project (OAP) to help employees understand the facilities and resources available for accessibility in the workplace. In addition, to get more employees involved in accessibility, Google supports and encourages the Disability Alliance Employee Resource Group (DERG), a self-organized group of employees.

This resource group is also very active in the China office, with activities such as matching mentors with people with disabilities, conducting 1-to-1 workplace development coaching, and inviting Alliance staff to participate in the design of office accessibility renovations.

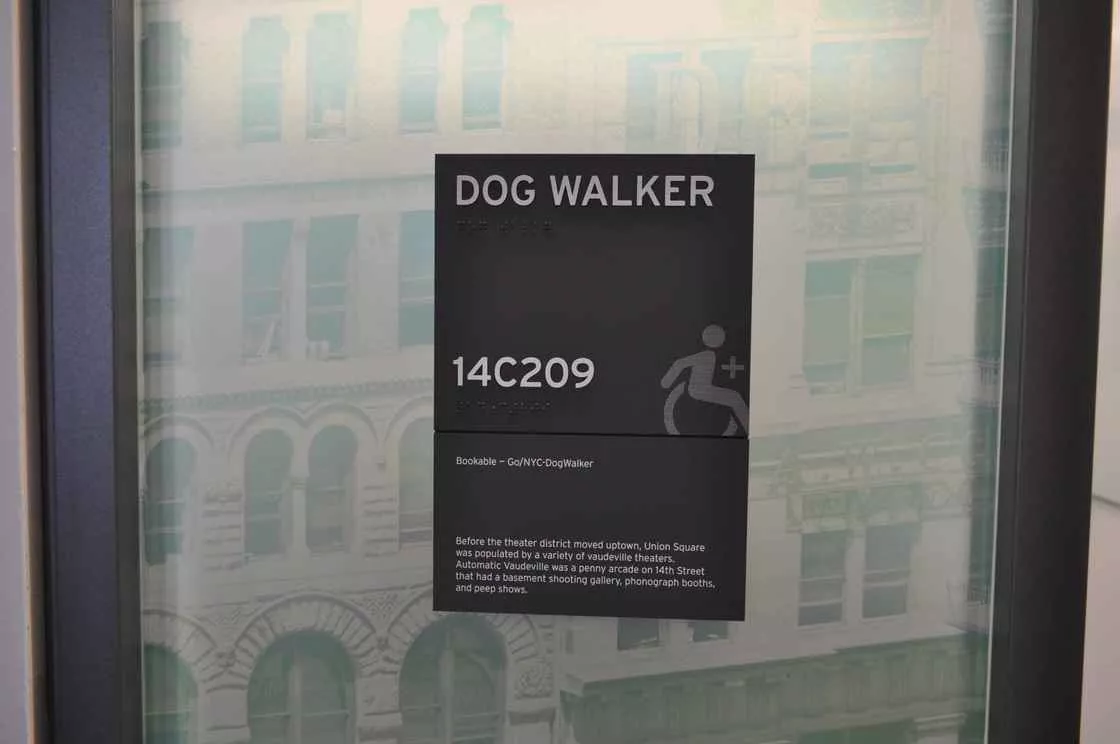

Signage adapted to Braille wayfinding in Google's Chelsea, New York officeNext, Anderson discusses the potential conflict between accessible design work and regular business potential conflicts between accessibility design work and regular business. She said that Google does a lot of internal coordination to minimize friction between teams. For example, accessibility-related content and components have been integrated into Google's design system, Material Design, and accessibility considerations have been incorporated into Google's development environment, design tools, and release process.

Signage adapted to Braille wayfinding in Google's Chelsea, New York officeNext, Anderson discusses the potential conflict between accessible design work and regular business potential conflicts between accessibility design work and regular business. She said that Google does a lot of internal coordination to minimize friction between teams. For example, accessibility-related content and components have been integrated into Google's design system, Material Design, and accessibility considerations have been incorporated into Google's development environment, design tools, and release process.

She also gave the example that to keep accessibility testing from slowing down the pace of product development, her team assembled a permanent test user group of non-Google employee users from around the world to provide regular feedback and participate in testing and research.

During the sharing, a media colleague asked about the role of disabled engineers on the Google team. In response, Anderson clarified that Google does not purposely recruit people with disabilities and assign them a special role, but rather treats them all equally. She gave the example of an engineer on her team who has a hand disability and cannot type, but thanks to Google's accessible technology and workplace environment, he can smoothly write code and answer emails using his voice. There is also a blind engineer who is responsible for managing the entire test team.

Accessibility features for the benefit of all

Anderson also focused on sharing Google's thinking on developing accessibility features - for the benefit of all. She suggested that some features were developed initially for the needs of people with disabilities, but have since been rolled out to become mainstream, making them accessible to the average user.

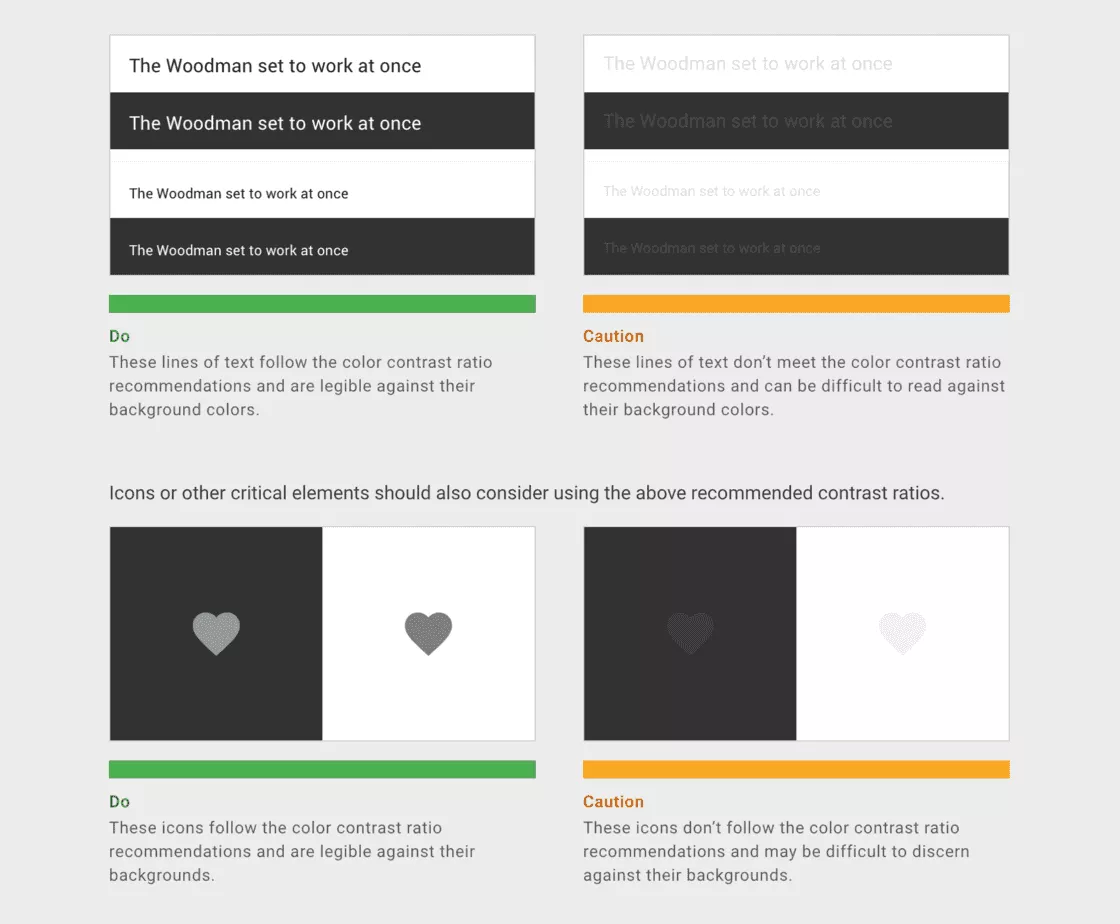

For example, the 'High Contrast' feature was initially designed for the partially sighted, but is actually very helpful in reading screen content in sunlight. Similarly, the real-time captioning feature is a great convenience for hearing people in noisy environments, and the larger touch response area in the interface design makes it easier to tap on target buttons in crowded environments such as subways.

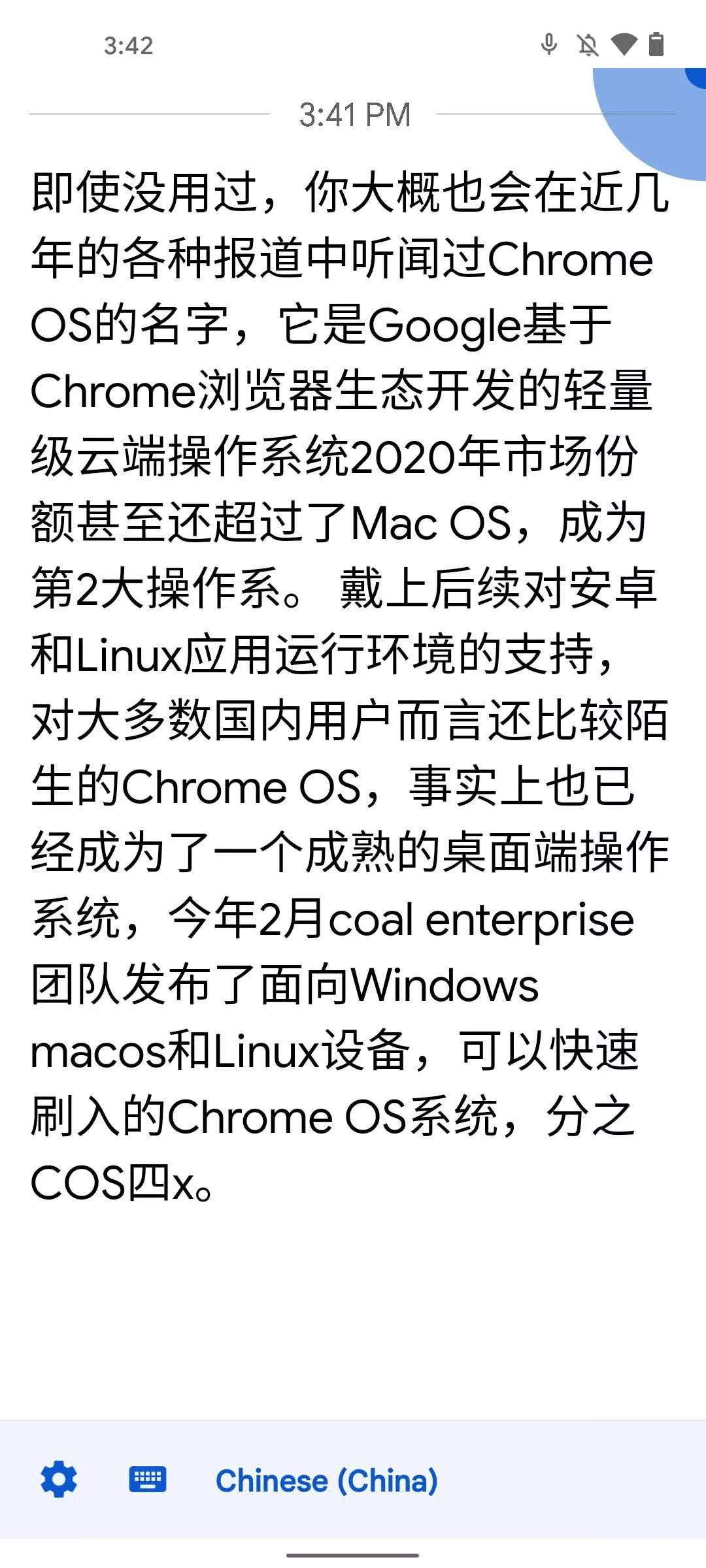

However, Anderson's 'personal favourite' is the 'auto complete' feature in the input method. This actually started out as an accessibility feature, but they have since found it to be quite beneficial for office workers typing on the go as well. She laughs that she can barely type without this feature.

However, Anderson's 'personal favourite' is the 'auto complete' feature in the input method. This actually started out as an accessibility feature, but they have since found it to be quite beneficial for office workers typing on the go as well. She laughs that she can barely type without this feature.

During the Q&A session, Anderson also discussed the relationship between the two design approaches of "designing products for people with disabilities" and "incorporating the needs of people with disabilities into products". She said that Google will adopt both ideas, but relatively prefers the latter integration idea, because it can help the disabled group have a sense of psychological "inclusion", that is, using the same products as their colleagues, classmates and friends. In other words, Google wants accessibility features to bring people together better, rather than artificially separating them.

We also asked Anderson specifically about his thoughts on the 'fragmentation' of the Android platform: does the wide variation in features and updates from manufacturer to manufacturer pose a challenge for Google in pushing accessibility features?

In response, Anderson acknowledges that this is a glaring problem, namely that there is no guarantee of 100% support for all hardware. But she points out that Google does a lot of work to ensure that accessibility goes hand-in-hand: on the one hand, Google does a lot of communication with manufacturers to make sure they're aware of the new features the platform offers, and in many cases the code is open-sourced. On the other hand, the Google accessibility team also tests a wide range of phones and versions of the system; in fact, the purchase of these test devices is approved by her own hand. In addition, she pointed out that the apps mentioned are available on the Play Store and can be downloaded for free, even if they are not pre-installed by the manufacturer.

Examples of Google accessibility features

At the end of the sharing agenda, Anderson presented three actively updated accessibility features as case studies: the Live Transcribe, Lookout, and Project Relate.

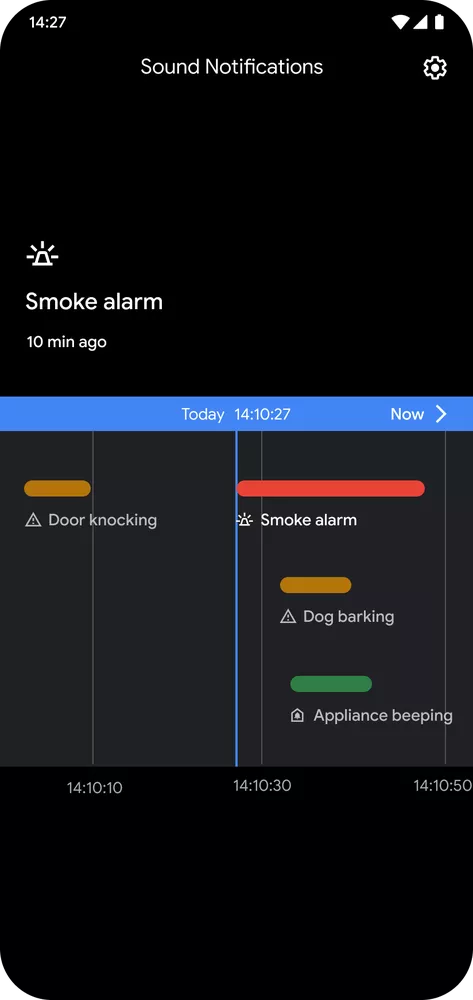

One of them, Live Transcribe (real-time transcription), was released in 2019 and is designed to transcribe speech quickly and accurately into on-screen text to help people with hearing loss have natural conversations. live Transcribe currently supports over 80 languages and dialects, as well as real-time translation between languages. Live Transcribe is also an open source tool, with code hosted on GitHub.

With the update, Google has also added to it the ability to detect sound-related events, such as showing a dog barking or knocking on the door, etc. This feature has since become a separate Sound Notification module that can recognize ten different sounds -- including baby sounds, running water, smoke and fire alarms, and electrical beeps.

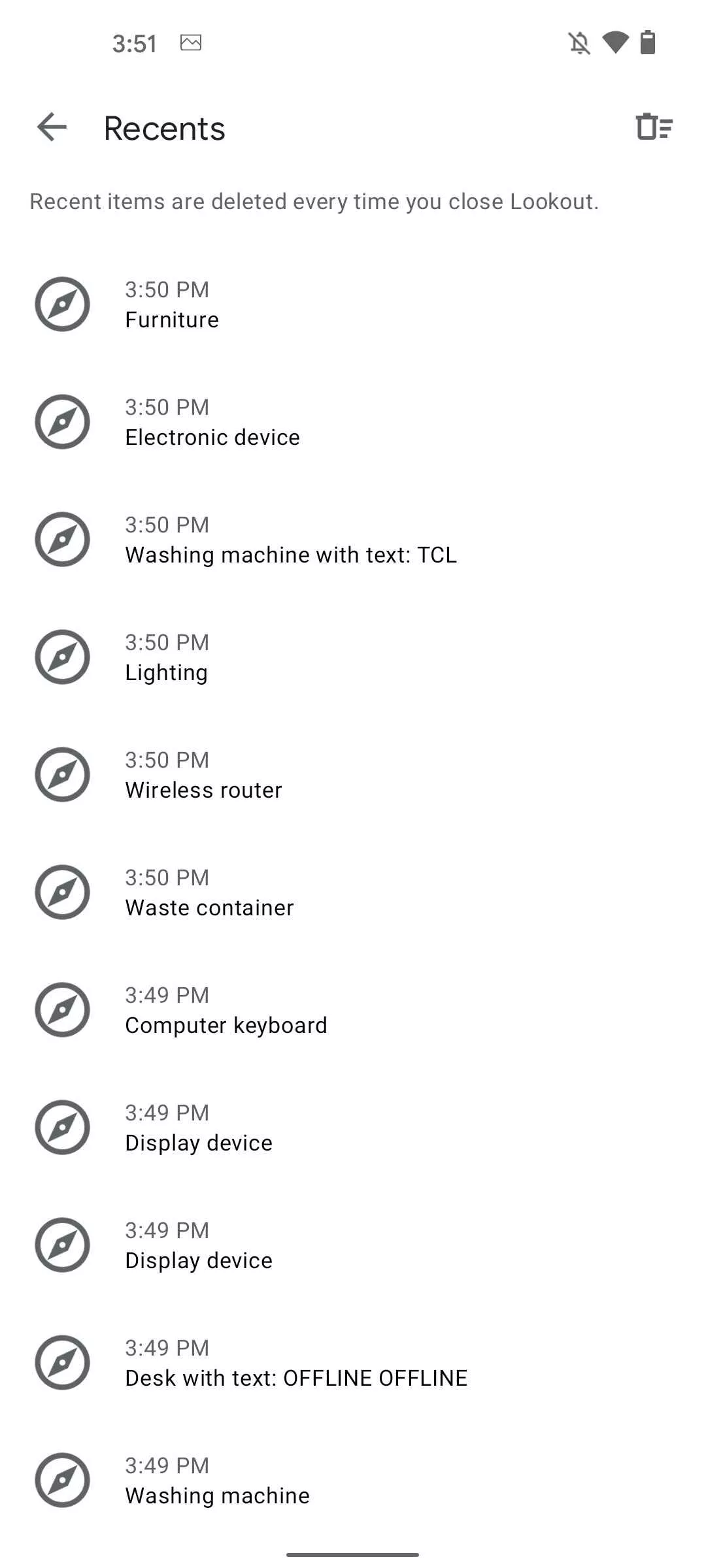

Lookout then rolls out initiatives/accessibility/lookout-app-help-blind-and-visually-impaired-people-learn-about-their-surroundings/) in 2018 to help users identify in their surroundings objects and information - text in books, locations of rooms and furniture, exit signs, people nearby, etc. Underlying Lookout is Google's machine learning framework [TensorFlow Lite] developed for mobile and micro devices (https://www. tensorflow.org/lite), and data processing can be done natively.

Lookout then rolls out initiatives/accessibility/lookout-app-help-blind-and-visually-impaired-people-learn-about-their-surroundings/) in 2018 to help users identify in their surroundings objects and information - text in books, locations of rooms and furniture, exit signs, people nearby, etc. Underlying Lookout is Google's machine learning framework [TensorFlow Lite] developed for mobile and micro devices (https://www. tensorflow.org/lite), and data processing can be done natively.

Initially, Lookout was somewhat experimental, supporting only English and requiring manual selection between "Home" "Work" and "Document" scenarios. and you had to manually choose between "Home", "Work" and "Document" scenarios. With subsequent updates, its functionality was refined, and features such as scanning food labels, reading handwritten text in locations such as Post-It notes and birthday greetings, and recognizing currency were added. (Unfortunately, Lookout does not currently support Chinese, and Anderson says it will gradually open up support for more languages as data is learned.)

Initially, Lookout was somewhat experimental, supporting only English and requiring manual selection between "Home" "Work" and "Document" scenarios. and you had to manually choose between "Home", "Work" and "Document" scenarios. With subsequent updates, its functionality was refined, and features such as scanning food labels, reading handwritten text in locations such as Post-It notes and birthday greetings, and recognizing currency were added. (Unfortunately, Lookout does not currently support Chinese, and Anderson says it will gradually open up support for more languages as data is learned.)

Lastly, Project Relate is relatively new, and is a test project that Google launched late last year to help people whose speech is affected by stroke, Parkinson's syndrome, and other conditions. In the test, Project Relate records a tester's voice through an app to learn their vocal characteristics, based on which it offers speech-to-text, speech synthesis and the ability to call Google Assistant to complete tasks (such as turning on lights and playing music).

Project Relate helps users take selfiesAnderson said that Project Relate is currently in invite-only testing in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Anderson said that Project Relate is currently being tested on an invite-only basis in four countries - the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand - and will gradually expand its user base as development matures.

Project Relate helps users take selfiesAnderson said that Project Relate is currently in invite-only testing in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Anderson said that Project Relate is currently being tested on an invite-only basis in four countries - the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand - and will gradually expand its user base as development matures.