Our brains rarely record single memories - instead, they store them in groups so that the recall of an important memory triggers the recall of other memories linked by time. However, as we grow older, our brains gradually lose the ability to connect related memories. Now, researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have discovered a key molecular mechanism behind memory connections. They also found a way to restore this brain function in middle-aged mice - and a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can achieve the same effect**

Published in [Nature] on May 25( https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04783-1 ) 》The results of the study in the journal show that this is a new method to strengthen human middle-aged memory and a possible early intervention for dementia.

Alcino Silva, a distinguished professor of neurobiology and psychiatry at the David Geffen School of medicine at UCLA, explained: "our memory is a huge part of our identity. The ability to connect relevant experiences teaches us how to stay safe and operate successfully in the world."

One thing about the basics of biology: cells are full of receptors. To enter a cell, a molecule must lock its matching receptor, which operates like a doorknob to provide internal access.

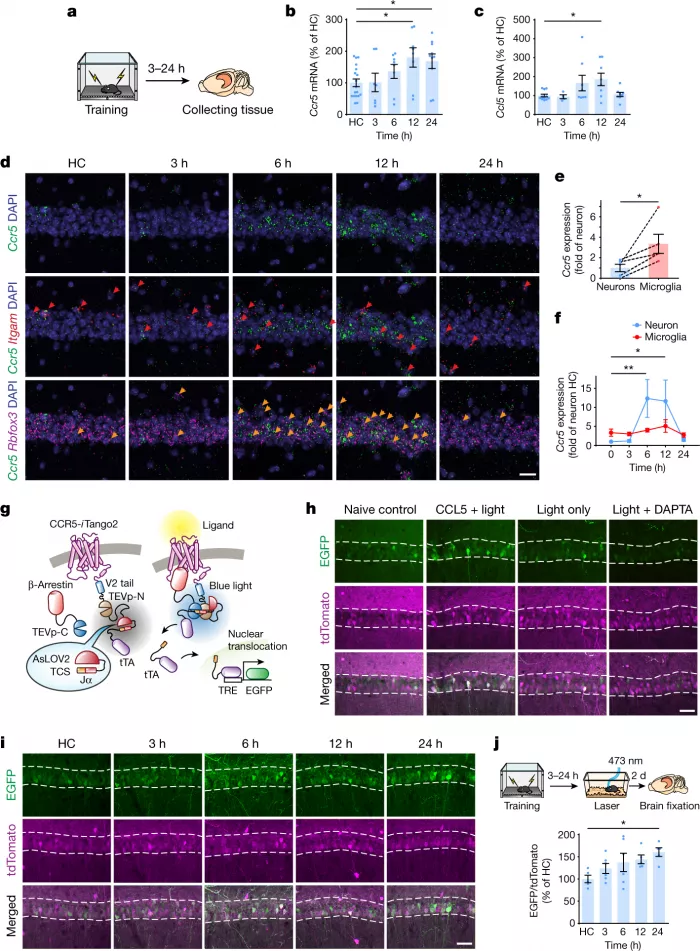

The UCLA team focused on a gene called CCR5, which encodes the same CCR5 receptor that HIV infects brain cells and causes memory loss in AIDS patients.

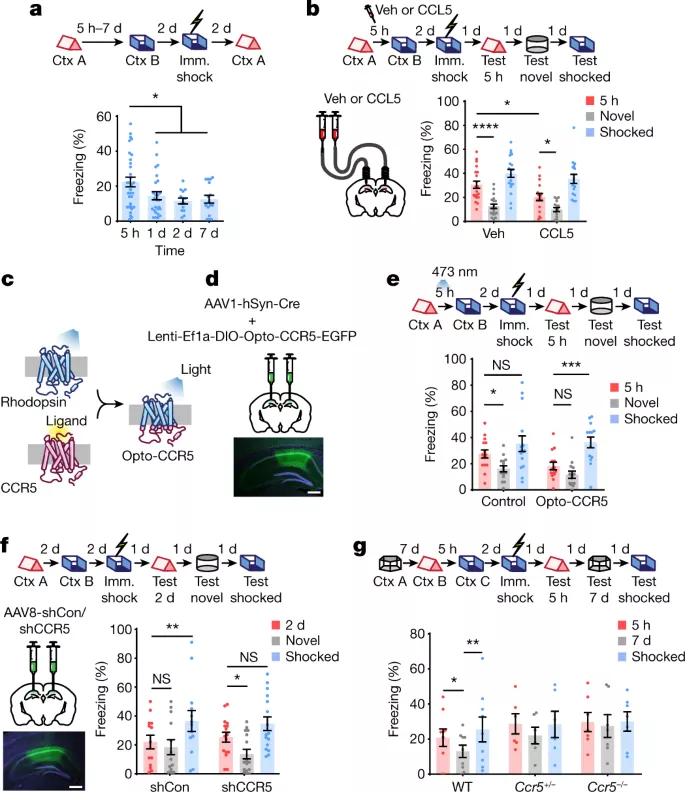

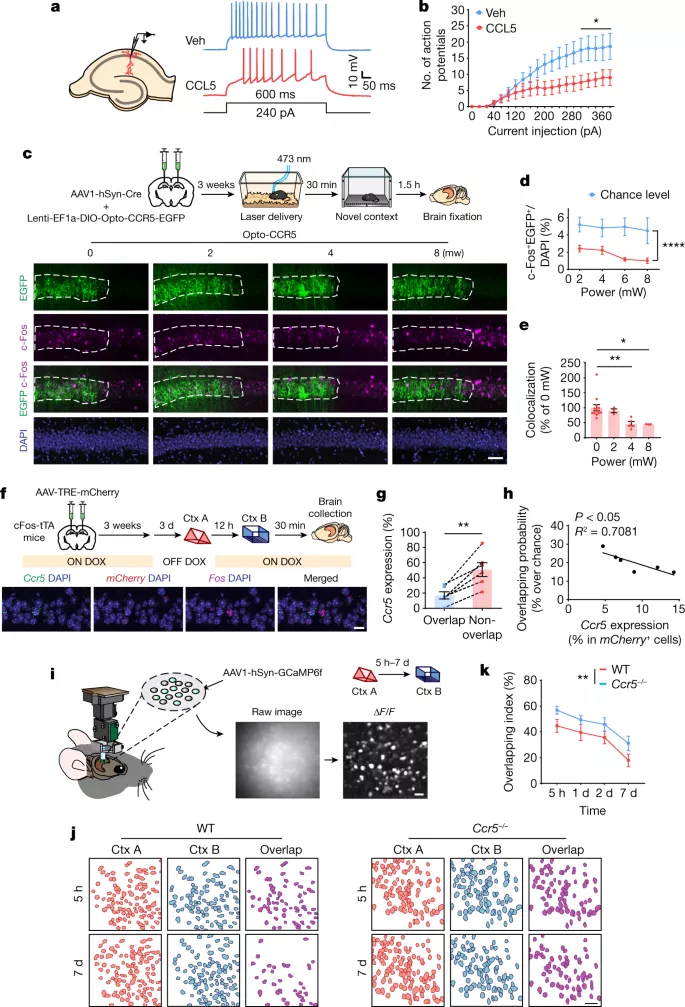

Early studies by Silva lab showed that the expression of CCR5 decreased memory. In the current study, Silva and his colleagues found a core mechanism for the ability of mice to connect their memories of two different cages. A micro microscope opens a window to the animal's brain, allowing scientists to observe the firing of neurons and create new memories.

Increasing the expression of CCR5 gene in the brain of middle-aged mice interferes with the connection of memory. The animals forgot the connection between the two cages. When scientists deleted the CCR5 gene in animals, mice were able to connect memories that normal mice could not connect.

Silva had previously studied malavero, a drug approved by the FDA in 2007 for the treatment of HIV infection. The researchers found that malavero also inhibited CCR5 in the mouse brain.

Silva, a member of the UCLA Brain Institute, said: "when we gave older mice malaviro, the drug replicated the genetic effect of deleting CCR5 from their DNA. Older animals can reconnect memories."

The findings suggest that malavero can be used off label to help restore memory loss in middle-aged people and reverse cognitive deficits caused by HIV infection.

"Our next step will be to organize a clinical trial to test the effect of malavero on early memory loss, with the aim of early intervention," Silva said. "Once we fully understand how memory declines, we have the potential to delay this process."

This raises the question: why does the brain need a gene that interferes with its ability to connect memory? "If we remember everything, life will be impossible. We suspect that CCR5 enables the brain to connect meaningful experiences by filtering out less important details," Silva said